Automatic Train Operation is a function that controls the traction and brake of the train, respecting the signalling and following the timetable for the mission to be executed, while controlling the train in the best possible way, thanks to the knowledge of the characteristics of the line and the train.

As well as reducing energy consumption, Automatic Train Operation makes it possible to standardise the running of a fleet of trains on a line, thereby reducing the time margins and allowing more trains to be used. ATO, coupled with a modern signalling system that reduces the safe spacing between trains to what is strictly necessary, means that the theoretical capacity of the infrastructure can be maximised. Let’s discover the principles of Automatic Train Operation its history and its future with an interoperable European solution.

For a clearer understanding of the concepts covered in this article, I suggest you first read the page presenting Automatic Train Protection.

Latest update: 2026-01

Automatic Train Operation by Bastian Simoni is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

1. Introduction

After discovering the grades of automation possible in the rail industry, we realised that GoA1 corresponds to the supervision of manual driving by an Automatic Train Protection (ATP) system.

Sometimes, as well as offering ATP, GoA1 can also offer driver assistance systems. These systems are not yet automatic pilots, but they come close, providing the driver with information to optimise traction and braking.

1.1 GoA1 and driving assistance

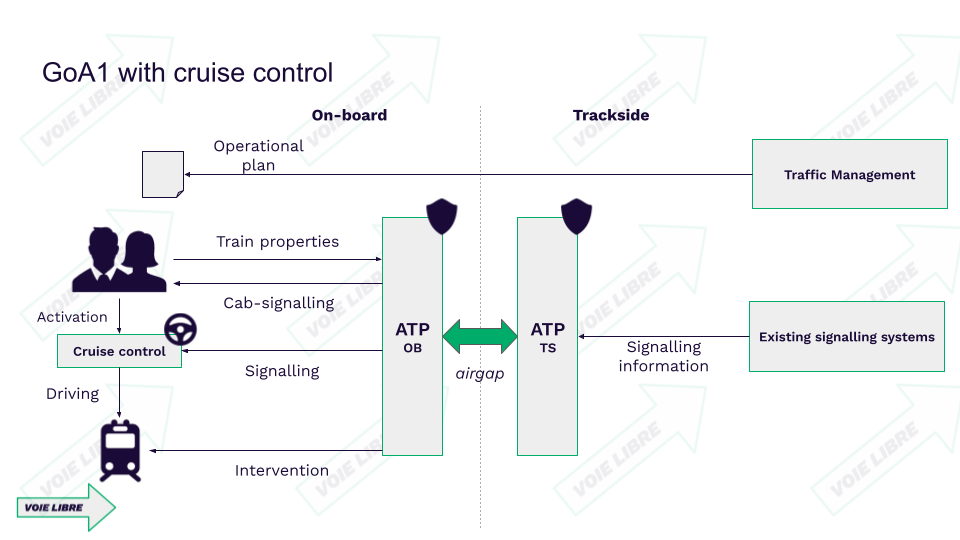

1.1.1 Cruise control

Cruise control is a comfort function sometimes offered to the driver.

Examples include :

- In France: imposed speed (Vitesse Imposée VI), an automatic system that follows a target speed set by the driver. As this automatic system is not controlled by the ATP, it can be de-activated by the ATP at any time if the imposed speed exceeds the speed limit authorised by the ATP.

- In Germany: the AFB (Automatische Fahr- und Bremssteuerung), which, combined with the German LZB high-speed ATP, pulls and brakes the train, following the speed limit imposed by the ATP. In this way, the connection between the ATP and cruise control prevents the ATP from taking control of the train.

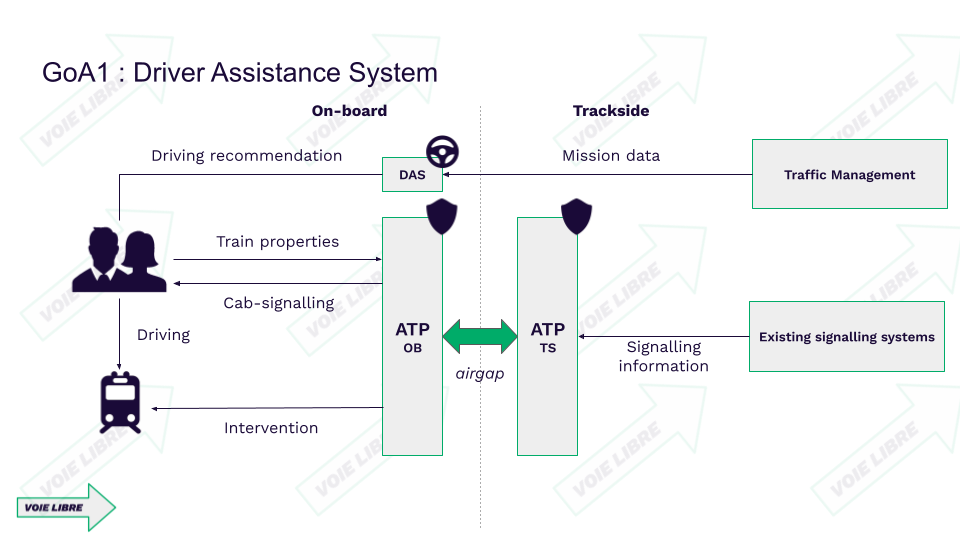

1.1.2 DAS

The DAS (Driver Assistance System) is a digital train driving assistance system. It tells the driver in real time how to drive his train (traction and braking indications), according to :

- The train’s position on the track plan (the DAS is generally an app installed on a tablet equipped with a GPS receiver),

- The properties of the track plan (ramps, gradients, curves),

- The timetables to be respected for the mission to run smoothly.

The DAS application installed on the tablet retrieves mission data from the traffic management system. This retrieval can be done once a day or continuously. When the DAS continuously retrieves mission data, it is known as a Connected DAS (C-DAS).

The DAS is an interesting tool for supporting drivers in implementing eco-driving, by coasting as much as possible.

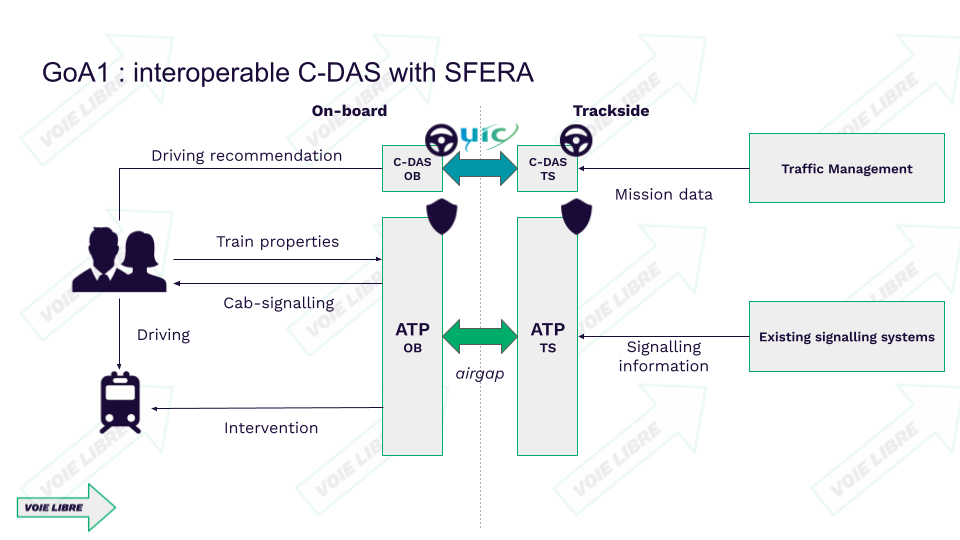

Many railway undertakings have equipped their drivers with tablets, with applications offering DAS functionality. This situation is similar with Automatic Train Protection systems, which have proliferated throughout the European Union without harmonisation.

To avoid making the same mistakes as with ATPs, the International Union of Railways (UIC) has launched a process to standardise connected DAS (C-DAS), and more specifically the track to train interface: the airgap.

The SFERA protocol has been developed to provide an interoperable C-DAS with a standardised airgap. This is made possible by the introduction of a C-DAS application on the trackside, which enables the existing traffic management system to be adapted to the standard format. The connection between C-DAS Onboard (C-DAS OB) and C-DAS Trackside (C-DAS TS) is usually made via public mobile network.

In this way, when the train crosses a border, the C-DAS on board the train disconnects from the C-DAS Trackside in country A, to connect to the C-DAS Trackside in country B, and retrieve the mission data from country B.

In 2024, many railway undertakings and infrastructure managers have started migrating their specific DAS to interoperable C-DAS compliant with the SFERA protocol. This will allow continued use of the C-DAS for international journeys.

1.2 Towards GoA2

In this introduction, we have understood that GoA1 is not limited solely to supervising driving. Driving assistance systems can also be offered in GoA1. These include:

- Cruise control, which can be controlled by the ATP or not,

- DAS, which tells the driver how best to drive his train, according to the timetable of the mission, in order to save energy. As the DAS was quickly adopted by railway undertakings to save energy, but without any harmonisation, the UIC launched a project to standardise the airgap, with the SFERA protocol. The aim is to enable the same DAS to be used in different countries, so allowing seamless border crossings.

The transition from GoA1 to GoA2 is made by using an automated system, based on cruise control and C-DAS functions, to control the train directly: this is ATO (Automatic Train Operation). Let’s discover ATO and the principles of GoA2 in the next chapter.

2. GoA2, automated driving with a driver in cab

2.1 ATO principles

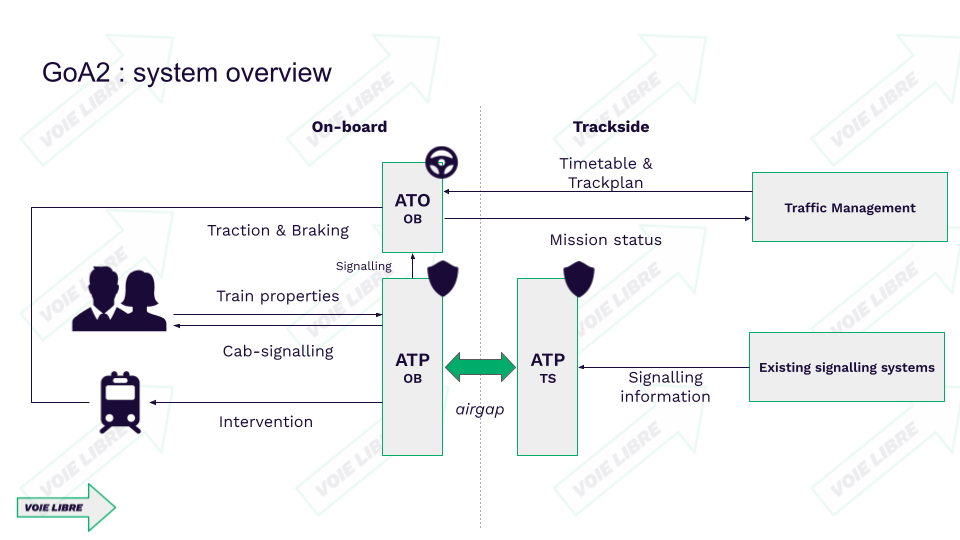

In GoA2, a device called ATO controls the train’s traction and braking. The driver is present in the cab, and is responsible for :

- engaging the ATO

- monitoring the passenger exchange at the station,

- monitoring the track, particularly in the event of an obstacle,

- managing any degraded situation.

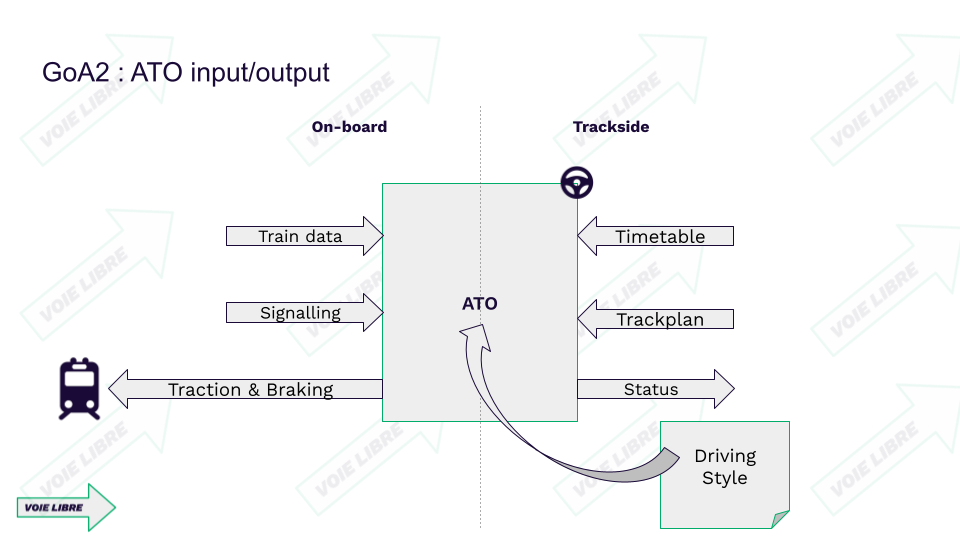

The ATO’s role is to control traction and braking of the train. To do this, it relies on a certain amount of input data:

- The signalling applicable to the train: the ATO must ensure that its driving complies with the signalling requirements. If it does not comply with the signalling, the ATO will cause the ATP to intervene, as in GoA1.

- The mission timetable to be respected: this is the equivalent of the GoA1 timetable. With the timetable, the ATO knows what time it has to pass a given point.

- Track plan data: this is a description of the tracks the ATO will be using. With this information, the ATO can “see far ahead” and anticipate how it will control the train.

- Train properties, such as length, weight, braking characteristics, etc. With this data, the ATO can adapt its driving to the type of train.

- Driving style: this is the way in which the ATO has been optimised to produce the optimum driving style for the type of train and the mission. Driving style is a differentiating factor among manufacturers, and represents genuine expertise.

As output, the ATO will control the traction and braking of the train. It will also send a periodic report to trackside traffic management, on the current status of mission execution: on time, early, late. This periodic report closes the traffic management control loop, enabling overall optimisation of operations on the railway network.

The ATO requires a large amount of input data to perform its automatic traction and braking function. To retrieve all this information, the ATO interfaces with :

- A Traffic Management System, which provides the ATO with up-to-date timetable and track plan data. This continuous link enables the ATO to have an up-to-date execution plan at all times. In return, the ATO periodically sends the execution status of the mission. This interface is dedicated to operations: it enables supervisors in the control centre to have an overall view of the ATO-equipped trains on a line. In the event of disruption, supervisors can take decisions that are immediately applied to the ATOs concerned, by sending a timetable update,

- The ATP, which provides the ATO with the applicable signalling information,

- The driver, who interacts with the ATO (to enter train data, engage or disengage the ATO, for example),

- The train, via its control and command system, the TCMS (Train Control & Monitoring System). It is via this interface that the ATO sends traction and braking commands.

2.2 Benefits

2.2.1 Energy efficiency

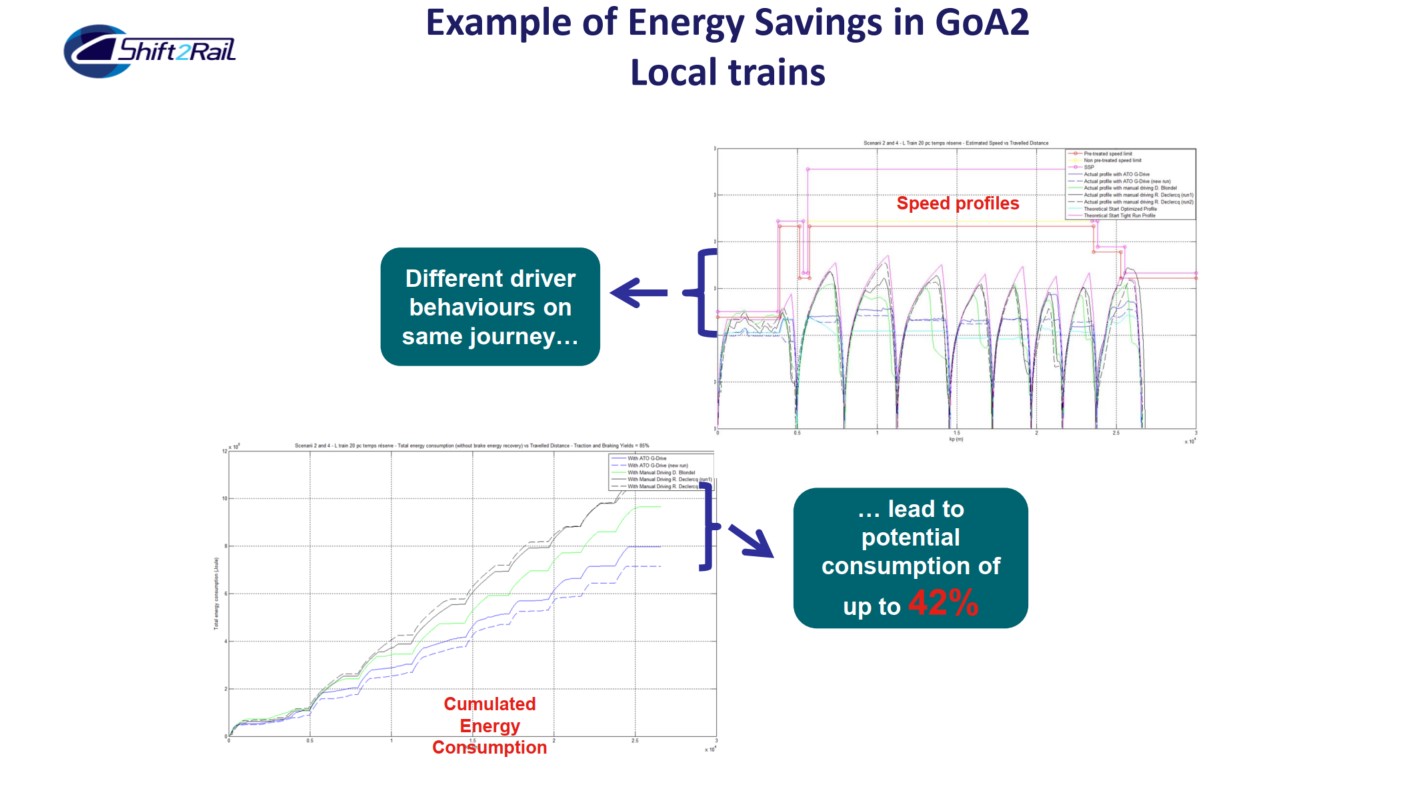

The on-board ATO has one advantage: it can “see far ahead” thanks to the knowledge of the timetable and the characteristics of the track being used (gradients, ramps, curves). In addition, the on-board ATO is configured by the mission and the driver according to the train’s characteristics (train category, length, weight). With all this data, the algorithm is able to control traction very precisely and use coasting as much as possible.

Another source of savings lies in optimising the use of rolling stock. By optimising driving, the ATO can reduce wear and tear on the train, and thus cut maintenance costs.

In a presentation given to the European Rail Agency in 2017, two examples highlight possible reductions in energy consumption by standardising driving profiles with the ATO on a fleet of trains:

- On intercity trains, this could lead to potential savings of up to 15%,

- On suburban services, potential savings of up to 42%.

2.2.2 Maximum use intensity of the infrastructure capacity

The railway infrastructure provides a theoretical capacity (number of trains per hour and per direction), which is essentially a function of the signalling systems and the safe distance imposed between two trains. As the ATO is a computerised system connected to the ATP, it is able to approach the limits imposed by the signalling as closely as possible. This is not the case with manual driving, where the driver will have his own margins (depending on his experience), so as not to be caught out by the ATP. On the scale of a line, a fleet of ATO-controlled trains therefore tends towards the theoretical capacity of the infrastructure, intensifying its use.

Moreover, if all the trains on a given line are piloted by ATOs, then the way in which the fleet of trains is driven is homogeneous. As a result, disparities in the way trains are driven are greatly reduced. Harmonised train driving on a line reduces the time dispersion in the execution plan. This opens up the possibility for the infrastructure to reduce the time margins between trains, and therefore to add one or more trains per hour and per direction.

The use of autopilot therefore allows a high use intensity of the infrastructure, by coming very close to the signalling safety envelope, and by allowing a reduction in time margins thanks to the harmonisation of train operation on the line.

Note: allowing safe spacing to be reduced to a strict minimum is THE factor that enables a line’s capacity to be increased to its maximum potential. Hybrid Train Detection and Moving Block options of ERTMS/ETCS are answers to this.

2.2.3 Operational responsiveness

The digital interface between the ATO and the Traffic Management enables operations to be highly reactive (and even proactive) in the event of network disruption.

The Traffic Management knows the theoretical timetable to be run. It also knows the status of all the ATOs it supervises, thanks to the status sent periodically by the ATO to the Traffic Management.

With this information, the Traffic Management can identify potential future disruptions on the network, if a train is ahead or behind schedule (via ATO status information). In this way, the supervisors, assisted by the Traffic Management, can optimise the operation of the line in real time, by sending mission updates to the ATOs concerned.

The ATO and Traffic Management duo is an emblematic example of the gains in operating responsiveness offered by the computerisation, digitisation and automation of the rail system.

2.3 GoA2 : getting started with metros

2.3.1 Historical background

ATO has a long history in the urban world. The first metros were equipped with automatic piloting in the 1960s.

At that time, the systems were analogue. The metro automatically pulled and braked according to a driving profile recorded in advance in mats on the ground. This was the principle used by RATP’s PA 135 system. By 1979, 90% of the Paris metro network was equipped with automatic piloting. [4]

2.3.2 Communication Based Train Control

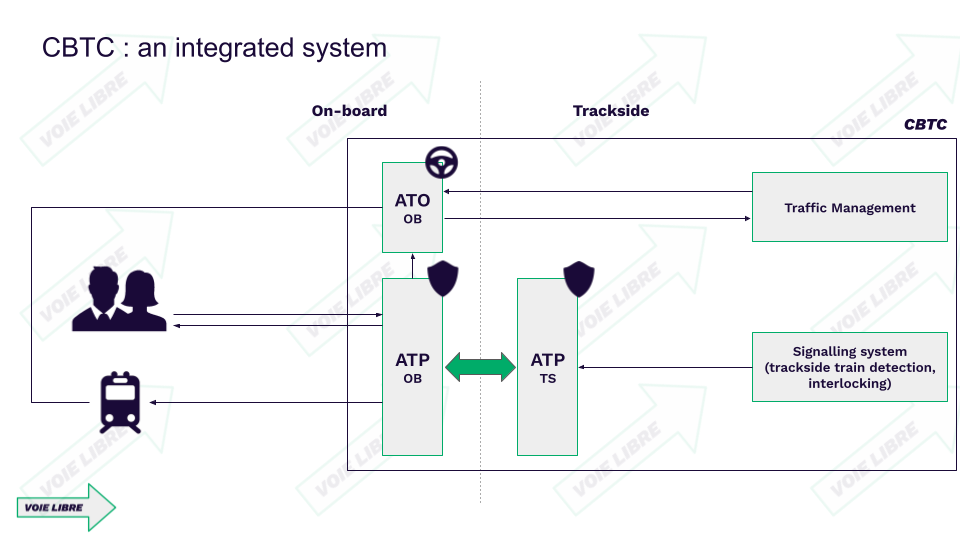

Analogue systems were gradually deprecated by the arrival of digital solutions in the 1990s. The system most used by metros today is called CBTC (Communication based train control). It is an integrated system, with a permanent radio link between the metro and the trackside installations. It offers ATP and ATO functions, as well as Traffic Management Systems (TMS). Fundamental signalling systems such as interlocking and train detection can be part of the CBTC.

CBTC is usually an integrated system. The same manufacturer provides ATP, ATO and Traffic Management. The advantage of an integrated system is that the manufacturer has full control over the design of the overall solution, and can make the necessary technical trade-offs to ensure that the system as a whole achieves the required performance.

On the other hand, it is a proprietary system. As a result, the operator and the infrastructure are dependent on the manufacturer who supplied the CBTC solution. This is known as vendor lock-in.

In the case of a metro line, this does not necessarily pose a problem. As the metro line is a clearly defined area, with rolling stock generally assigned to that line, an integrated system makes sense: the priority is performance. And in the context of the metro, performance is the interval between two metros (headway), allowing a high number of passengers per hour and per direction (PPHPD).

On the other hand, on the national rail network, implementing a proprietary solution is prohibited. In accordance with Directive 797/2016, all the EU’s national rail networks must work towards a Single European Railway Area. Interoperability is therefore the priority on the national rail network.

We will see this with the new playground for automatic piloting: suburban and French RER trains, some of which run on the national rail network.

In order to enable citizens of the Union, economic operators and competent authorities to benefit to the full from the advantages deriving from the establishment of a single European railway area, it is appropriate, in particular, to improve the interlinkage and interoperability of the national rail networks as well as access to those networks and to implement any measures that may be necessary in the field of technical standardisation as provided for in Article 171 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

2.4 Suburban lines: the new playground for ATO

2.4.1 RER A: the first application of GoA2 in suburban areas in France

With 308 million passengers a year, and 50,000 passengers an hour in the central section (in each direction and at peak times), the RER A is a very busy line, and an important one for the Île-de-France public transport system. [5]

To cope with the increase in passenger numbers and boost performance on the central section, RER A was first equipped in 1989 with an ATP offering the cab signalling function: the SACEM. In 2018, automatic piloting on SACEM was introduced on the central section, between Nanterre-Préfecture and Val-de-Fontenay / Fontenay-sous-Bois, where passenger numbers are highest.

So, after being used for a long time on metros, automatic piloting is making its entry into the world of superurban transport with the RER. [6]

Passenger load on each branch. We can see that the passenger load is highest on the central section, where SACEM and then automatic piloting have been deployed. Source

The introduction of automatic piloting on SACEM in 2018 offers, according to the manufacturer, an improvement in regularity and a time saving of 2 minutes on the average journey between Vincennes and La Défense stations. [6]

However, SACEM is a proprietary system introduced in 1989, and the SACEM-compatible ATO deployed on RER A trains remains a specific product. So deploying this type of proprietary system for other RERs no longer makes sense today, since interoperability is necessary. Let’s find out what solution has been identified for RER E to meet this requirement.

2.4.2 RER E and the NExTEO system: a compromise between performance and interoperability

We have seen that CBTC is an interesting solution for increasing the capacity of a line by combining ATP/ATO/TMS functions. This integration of functions into a global solution gives manufacturers a certain degree of freedom to design their system as best they can to meet the customer’s performance requirements.

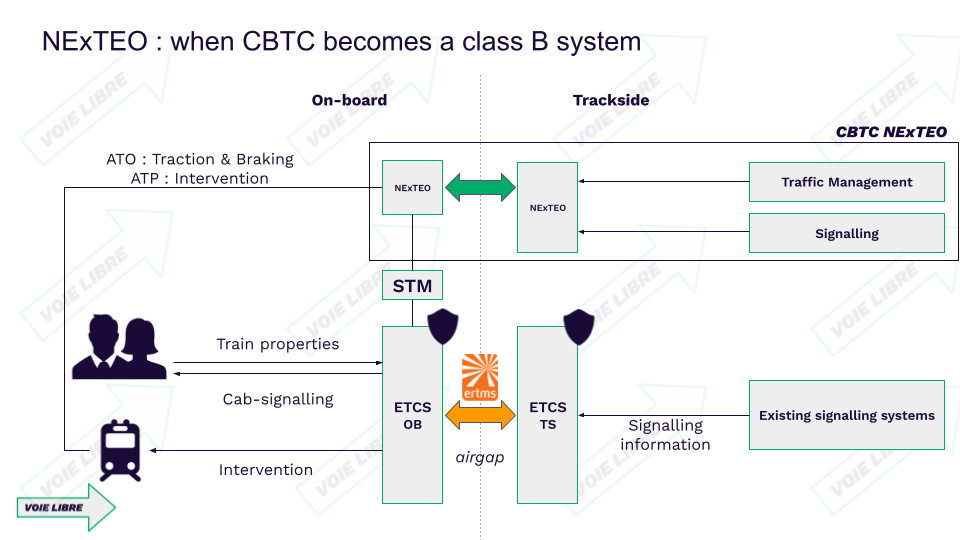

On the other hand, the CBTC is proprietary and cannot be installed on the national rail network. The national rail network must fit into the single European railway area. Consequently, only one type of ATP must be used, the European standard ATP: ERTMS/ETCS.

The national ATPs installed before the creation of ERTMS/ETCS are class B systems. When ERTMS/ETCS was created, it was planned to make it compatible with class B systems, so that the systems could coexist during migration. For a better understanding of this aspect, I refer you to this paragraph of the article on ERTMS/ETCS.

In the case of the RER E, we have a central section in Paris, which will only be used by RER E trains, and sections outside Paris, which are part of the national rail network. It is on the central section that the need for capacity will be greatest, as it is on RER A.

Map of RER E. Source

With this in mind, let’s apply the following reasoning:

- The central section is fairly isolated from the national rail network, will only see RER E trains, and could be equipped with a CBTC,

- The national rail network must be part of the Single European Railway Area, with the ERTMS/ETCS ATP,

- ERTMS/ETCS can be used in conjunction with a class B system, via the adaptation module (called STM),

- If the CBTC is considered a class B system, it can coexist with ERTMS/ETCS,

- As a result, RER E trains, which run on both the national rail network and the central section, could be equipped with ERTMS/ETCS (mandatory for all new trains today), and a CBTC qualified as a class B system.

This reasoning gave rise to NExTEO, a generic CBTC concept approved as a Class B system by the European Rail Agency (ERA). This approval is only valid for the Paris region. [7]

NExTEO is therefore an interesting concept, in that it makes it possible to take advantage of the benefits offered by CBTC in areas of the rail network where there is a very high level of use, and where a NExTEO Class B system can be deployed (Île-de-France). Compatibility with ERTMS/ETCS means that CBTC and ERTMS/ETCS can coexist on board trains.

This concept can be applied in the context of a central section crossing Paris, such as the RER A and E. This is why NExTEO will also be deployed on RER B and D. [8]

On the other hand, for RERs that make full use of the national rail network, and where a proprietary system is impossible to implement (the ERA’s approval of NExTEO being valid only in the Île-de-France region), we need a standardised and interoperable ATO. This is where the interoperable European autopilot comes in: ERTMS/ATO.

Synthesis

In the GoA1 grade of automation, driving assistance offer speed regulation and the display of driving recommendations for eco-driving. All under the constant supervision of the automatic train protection system.

In GoA2, a device enables the train to be driven automatically, taking into account a range of input information: the timetable for the mission, as well as the signalling information to be observed.

Automatic driving offers clear benefits. It reduces energy consumption through optimised driving. As the ATO algorithm is connected to the ATP, it can drive as close as possible to the limits of the signalling, and therefore intensify the use of the infrastructure. It also enables a fleet of trains to be driven in a uniform manner, which reduces the time dispersion in the execution plan. This frees up additional capacity, which can be used to inject more trains.

These benefits have motivated the introduction of automated driving in fairly homogeneous and closed environments: metros. Integrated, proprietary systems known as CBTC are used on a massive scale. However, CBTC cannot be used on the national rail network, as interoperability is mandatory. This is why an interoperable European automatic train operation system has been developed: ERTMS/ATO.

Next article : ERTMS/ATO, the interoperable autopilot

Crédit photo de couverture : Bastian Simoni.

Références :

[1] https://securite-ferroviaire.fr/la-securite-ferroviaire/comprendre-la-securite-ferroviaire

[2] https://www.ertms.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ERTMS_Factsheet_8_UNISIG.pdf

[3] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32016R0919

[4] https://voie-libre.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/DP-le-groupe-RATP-leader-mondial-du-metro-automatique.pdf

[5] https://www.ratp.fr/travaux-ete-rer/les-chiffres-cles-du-rer

[6] https://www.alstom.com/fr/press-releases-news/2017/5/alstom-a-debute-avec-succes-la-mise-en-service-du-pilotage-automatique-sur-le-rer-a

[7] https://voie-libre.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/List-of-CCS-Class-B-systems.pdf

[8] https://www.alstom.com/fr/press-releases-news/2023/11/alstom-remporte-un-contrat-de-300-millions-deuros-pour-equiper-2-lignes-rer-en-ile-de-france-avec-la-derniere-technologie-de-signalisation-nexteo